Exercise

Review the paper “Territorial Photography” by Joel Snyder, published in the book “Landscape and Power” by Mitchell, W.J.T. (2002). The University of Chicago Press.

Review of Paper

Snyder starts by stating that when photography was first emerging (1830s) people were unsure what it is was for or how it should be considered. By the 1850s the technical processes being used for landscape meant that the images were now sufficiently different from other forms of picture that they were now distinct. Images now looked “machine made” and were therefore lauded for their detail and accurate representation of scenes. At this stage, photography was not thought of as art and so did not rival painters for example. Images of this era were assessed on the likeness of the image to the actual scene itself – the image is simply a “passive recording”.

With this prevailing philosophy Snyder seeks to investigate two prevailing practices of the 1860s and 1870s to understand why the images look the way they do. He makes the point, he is not assessing the pictorial quality of the images, rather the “specificity of the approach”.

Snyder starts by identifying the first generation of landscape photographers (1840s and 1850s), for example Hewlett or Delamotte, and notes that their compositions inherit the conventional subject matter and representation of picture makers of other forms such as lithography. Snyder also notes that these images were for personal use and therefore not influenced by the demands of a buyer.

By the late 1850s, there was a definable market for landscape images largely focussed on travel and landscape prints for tourists, prints being sold at the location of the images as keepsakes. This went on to expand as business began to sell each other’s images and so a national marketplace evolved.

Snyder takes the time to describe this evolution of the marketplace because he wants to make the point that it was business, not art or any other motive, that drove the evolution of the imagery. The style of image that sold the most is what would be captured the most. Snyder cites Yosemite Part images by Carlton Watkins, Utah landscapes by Charles Savage, and Railroads by Andrew Russell.

This business though does not explain why the images were what they were; other styles of image could have sold equally well. Snyder notes that the first generation of landscape photographers were from “privileged classes” and therefore likely to be schooled in art and the traditional painters of landscape, he fells that perhaps they could not see beyond that tradition. Snyder quotes Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, an art and photography writer, whose view was that “a picture has aesthetic merit only insofar as it is to the what she calls ‘our experience of nature’”.

Given that photographs are man made objects they could not claim aesthetic merit and therefore could not have artistic potential. At the same time period as Eastlake’s comments, bodies such as the Royal Photographic Society were favouring images that had technical excellence, and were produced with a glossy, machined-like, appearance. Something that looked mass produced. I think that this would favour the perception that there was nothing artistic or aesthetic in such a manufactured item. This all led to the distancing of photography from fine arts.

This distancing meant that the next generation of photographers were “freed” from the need to follow conventions and the classical approach to portraying a landscape. They were free to capture what they liked, how they liked. Images instead judged for accuracy and “life likeness”. Any comment on aesthetics were of the scene itself and the technical ability of the photographer. To quote Snyder “the rhetorical question facing any would be landscape photographer was a rather difficult one: how to make a picture that was resolutely photographic yet, at the same time, beautiful or stunning … but that nevertheless could be convincingly experienced as a conventional, a product of … photographic craft”. I must admit, I have faced this question myself.

Snyder begins by considering Carlton Watkins and his imagery in Yosemite Park. His images were large, flawless, and technically perfect; an approach that inspired others such as Ansel Adams. Commentary on his images talk of the technical perfection but also have the accurate capture of the view, in such a way as anybody could have seen the view. It is the view that makes the image, the image is an accurate and disinterested representation of the sight that anybody could have seen, and this there is no artist’s imagination at play, simply the accurate capturing of the view.

Watkins was also commissioned by California’s Geological Society to assist with mining, lumber and railroad interests. Snyder talks of these images as aestheticised and “smoothed” to make the images visually attractive. Whereas in real life, the industrial works being carried out in places of natural beauty would of course be somewhat devastating to the land. To me this is therefore a far cry from his earlier images where the praise given to them was based on their accurate capturing of the scene without any artistic influence. As the scenes were not as aesthetic as depicted in Watkins’ images, it is clear that he used painterly traditions in his framing and production techniques to shift has paintings towards their genre. Perhaps the viewers did not realise this to be happening and assumed the scenes were as depicted.

Snyder talks of the literature of the time commending the pictures for being faithful to nature and that the aesthetics were merely a coincidence arising from the pictorial nature of the scene being captured (not from Watkins’ use of landscape conventions).

During the period of 1867 to 1879, the surveying that led to Watkins’ images transitioned from army surveys of unknown lands to “civilian surveys managed by scientists and engineers. O’Sullivan served as the photographer for two such expeditions and during the period and took a large number of photographs in the Great Basin of Nevada, Arizona, Utah and New Mexico. In contrast to Watkins’ images, they portray the landscape as “bleak, inhospitable … a godforsaken anesthetizing landscape. “.

O’Sullivan was commissioned to capture the landscape, he was not concerned with selling his prints. This gave him freedom to abandon any concern with beauty or the ‘attractiveness’ of the images he captured.

Snyder discusses that the style of O’Sullivan’s images have made them difficult to place or categorise but some have claimed that they are a precursor to a modernist photographic practice. Roasalind Krauss disagrees and by claiming that the work is essentially scientific and that the images are scientific views rather than landscape images. She claims that as such, they come from a different ‘discursive space’ and therefore cannot be compared to that of a painter. Essentially she is attempting to remove the images from being art, or of “pictorial character”.

An image of O’Sullivan’s shown in Snyder’s paper is Sand Dunes near Carson City. In it we see his portable dark room crossing an apparently vast sand dune; apparently so because we cannot see the edges. In fact, the picture is misleading, the dune is more a small mound set in a flat plane. The images therefore leads the viewer to assume something that isn’t. This is in stark contrast to the praise given to Watkin’s images for their accurate representation of a what any person would see.

Reflection Points

- It is interesting that the imagery of the times appears to have been driven by what would sell. It is only when O’Sullivan did not need to consider this, that he was free to change the way in which his images were captured (although he still presumably needed to satisfy his fee payers.). I think this distinction still exists today, there is ‘art’ that is the aesthetic kind, probably intended for sale and art, the imaginative or expressive kind, which is probably not. This distinction is one of my greatest learning points studying with the OCA, I had never really understood the distinction. I was also worried that this distinction did not exist in landscape imagery – it almost stopped me studying this module – I am therefore glad to see that it does.

- I also find it interesting how the non-photographic community seek to claim that photographs are not art. In Watkins’ case the focus is instead on the technical skill of the photographer, with any aesthetic appeal being generated by the scene itself rather than the photographer. In O’Sullivan’s case, we see that he is using framing techniques to make a point, or to deceive the viewer. Whichever it is, he is consciously making a statement. I am reminded of the need to explain the art / commercial art distinction whenever I am explaining to friends and colleagues that my studies are about art and expression whenever they glance at some of my images and appear a little disappointed; illustrating that even now, 150 years on from the era Snyder discusses, it remains difficult to position landscape photography.

Example Images

Browns Park, Colorado – O’Sullivan

See Fig 1 for this image.

The image is taken from an elevated position, there is nothing in the foreground that is on the same level as the camera, it is as if I am floating. This approach leaves me feeling like I am going to fall into the picture, the same feeling as standing on a cliff edge with no fence in front of you. In turn this approach has enhanced the viewer’s perception of the height, or depth, of the valley that makes up the foreground. This enhanced height leaves one wondering how man could inhabit the area given the sheer size of the cliffs.

Feelings are enhanced further by the man in the foreground who first of all adds a sense of scale to the entire image but also is shown looking directly down the cliff face as if he is wondering how to get down to the bottom. The figure is also shown balanced quite precariously on a craggy outcrop, one wonders if he could fall which again exacerbates the feeling how difficult it would be to live in the area. Without forethought, this image could have been taken standing on the same level as the man but this would considerably lessen the effect and dramatic nature of the framing.

In the distance we can see flat planes. The river leads through the image in a classic landscape convention and in this case serves to lead the eye to this remoteness where there is no settlement to be seen at all. In summary, the interplay of the elevated position, the figure looking down the cliff and the river running to a desolate area all combine to create what looks like a difficult place to explore or inhabit. Presumably the object of O’Sullivan’s framing choices.

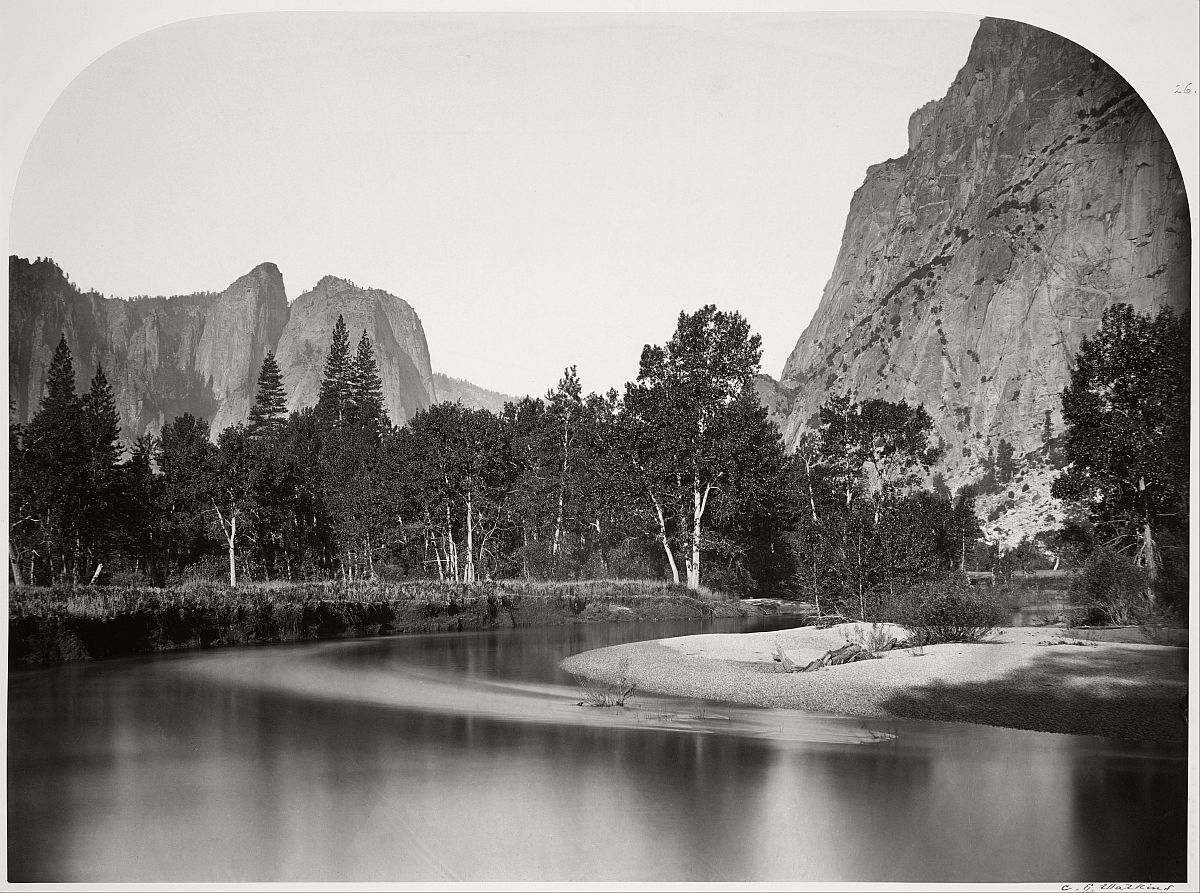

View From Camp Grove, Yosemite – Watkins

See Fig. 2 for this image.

In this image we see a river in the foreground and Yosemite rising in the background. The first thing that I notice is that the picture is taken at ground level, the view is the same as I would see if I had been stood there myself. Although I cannot see the river bank closest too me, I do not have the same feeling of falling into the image as I did with O’Sullivan’s because I am so close to being on the same level as the river itself. With the white water in the river being blurred we can see the image was taken with a long exposure, probably because of the high for a small aperture to achieve the sharpness of the images that can be seen front to back. This softening of the water means that we cannot see how fast the river is flowing but I am left feeling as if it is gently flowing along at a leisurely pace.

All in all, the scene looks like a nice place to visit despite the hugeness of the mountains in the background. It is easy to imagine oneself having a quiet picnic sitting on the banks of the river. Quite the opposite feelings to those evoked by Fig. 1. Finally, The sharpness of the scene and the exposure meaning nothing is pure black or white is a very good example of the technical excellence that Watkins strived for; this is an image that even today, with 150 years of technical advancement in camera capabilities, one would be proud of.

Images

Figure 1. O’Sullivan, T., 1872. Browns Park Colorado. [image] Available at: <https://petapixel.com/2013/09/02/amazing-19th-century-photographs-american-west-timothy-osullivan/> [Accessed 24 January 2021].

Figure 2. Watkins, C., 1861. View From Camp Grove, Yosemite. [image] Available at: <https://monovisions.com/carleton-e-watkins-biography-19th-century-landscape-photographer/> [Accessed 24 January 2021].